Laverie Vallee (stage name: Charmion), pioneer strongwoman and trapeze artist

I've always been attracted to strong women. I was six years old when I first saw Conan the Barbarian (the classic original starring Arnold, not the crappy remake). When I saw Sandahl Bergman fighting alongside Arnold as Valeria the Valkyrie, I was immediately enthralled. Despite being years away from finding the opposite sex interesting, seeing an athletic, genuinely strong woman was as enthralling as Arnold's massive chest and biceps. It was the same when, a year later, I gazed upon Virginia Hey in The Road Warrior ... and before you ask, yes, my parents let us watch pretty much anything growing up. A few years later, when I was eleven, Aliens became one of my favourite films. Sigourney Weaver was a bad-ass, though I was immediately drawn to Jenette Goldstein as Marine PFC Jenette Vasquez. The moment she started doing behind-the-neck pullups, I was enraptured. There are other examples, such as Linda Hamilton's impressively jacked physique in Terminator 2. All were fantastic characters who epitomised what it meant to be strong, physically and mentally, while still being vulnerable, flawed, and "human." They were neither damsels in distress, nor toxic misandrists. This made them relatable and likeable, demonstrating that strength could also be feminine.

When I was old enough to truly appreciate competitive athletes, both men and women, Karyn Marshall, became a personal favourite when it came to strength competitors. She won the first Women's World Weightlifting Championship in 1987 in the 82.5 kg (181.75 lb) weight class. She took home two of the four gold medals won by the entire U.S. team, winning both the Snatch (95 kg / 209.4 lbs) and Clean-and-Jerk (125 kg / 275.5 lbs). While the U.S. teams overall severely under-performed, with the men finishing 5th in medal count, and the women 4th, Karyn stood out, having bested every female competitor, regardless of weight class. Even the unlimited weight class winner, Han Changmei of China, finished with a combined total 10 kg (22 lbs) lower than Karyn, who earned the title World's Strongest Woman. Two years prior, Karyn was the first woman to ever clean-and-jerk over 300 lbs, with an astonishing lift of 303 lbs (137 kg). This earned her a place in the Guinness Sports Record Book, breaking the previous record that had stood for more than six decades.

Karyn Marshall being inducted into the USA Weightlifting Hall of Fame in 2011 by Arnold Schwarzenegger

A Millennia-long Road to Acceptance

When Karyn Marshall began training in 1978, there were no organised competitions for women weightlifters, who were regarded as more of a "freak show" than legitimate athletes. Karyn lamented in a 1987 interview with Sports Illustrated that, "People think women weightlifters are squat and muscle-bound, with all the intelligence of amoebas." Never mind she has multiple degrees, including a PhD. And to be fair, male weightlifters deal with the same stereotype to this day. One does not usually hear the term "gym bro" used as a compliment. And yet, men with a lot of muscle are still more accepted then women.

Indeed, the concept of physically strong women has faced roadblocks since the time humans first discovered strength training. The first gymnasiums of Ancient Greece had an expressed prohibition against women, who were neither allowed to train nor compete. The Romans were a bit more progressive, evidenced by a 4th century mosaic at the Villa Romana del Casale in Sicily, depicting women lifting weights and competing in various sports. And while they're all in bikinis, let's not forget that Ancient Greek (and sometimes Roman) men had to compete in the nude, without so much as a jock strap to keep their naughty bits in place!

Women were allowed to fight in the arena as gladiators, though the term "gladiatrix" is a modern invention. Like modern boxing and mixed martial arts (MMA), women only fought each other. Despite being the superstars of their day, the names of most gladiators are lost to history. Besides the famous Verus and Priscus from the opening games of the Flavian Amphitheatre (aka the Colosseum) in 80 A.D., two of the only other gladiators we know by name are a pair of women from the 2nd century. Called Amazon and Achillia (I'm guessing stage names), they "fought to an honourable draw." Their bout is commemorated on a stone carving now located at the British Museum.

Female athletes faced greater limitations during the Medieval and Renaissance Eras. Athletic competition was limited to "stick and ball" games, yet they were inexplicably barred from tennis courts. Football (i.e. soccer) was also out. Most other sports were deemed "un-feminine."

The rise of cycling during the 19th century (covered in a previous blog post), saw popularity amongst both men and women. Continuing on with absurd pseudoscience, doctors at the time stated that cycling could cause health issues in women, such as infertility and even tuberculosis! Hmm, I guess all that air pollution from the Industrial Revolution, or that most of the population smoked had nothing to do with people's lungs rotting.

Unperturbed, both bicycle and clothing manufacturers worked to accommodate female riders. Bicycles featured lower centre bars to account for the long dresses of the time, while special trousers and bloomers were made so women could properly ride without risk of skits becoming entangled.

It was during the late Victorian Era that a new physical fitness culture, one centred around strength and muscularity, began. Its most famous founder was Eugen Sandow, the Prussian bodybuilding and weight lifting pioneer, whose image is still used for the winning trophies of the Olympia Bodybuilding World Championships.

Sandow's rise began in the 1880s, though he certainly was not alone. Strongmen became an attraction at circuses, and it wasn't long before muscular women joined the culture. These performers being considered "freaks" and sideshows is probably the only reason women were not outright barred. Large, muscular men were still nearly a century from mainstream acceptance, yet for women the obstacles were much greater. In a world where men wanted to be seen as strong and dominant, powerful women were seen as a threat.

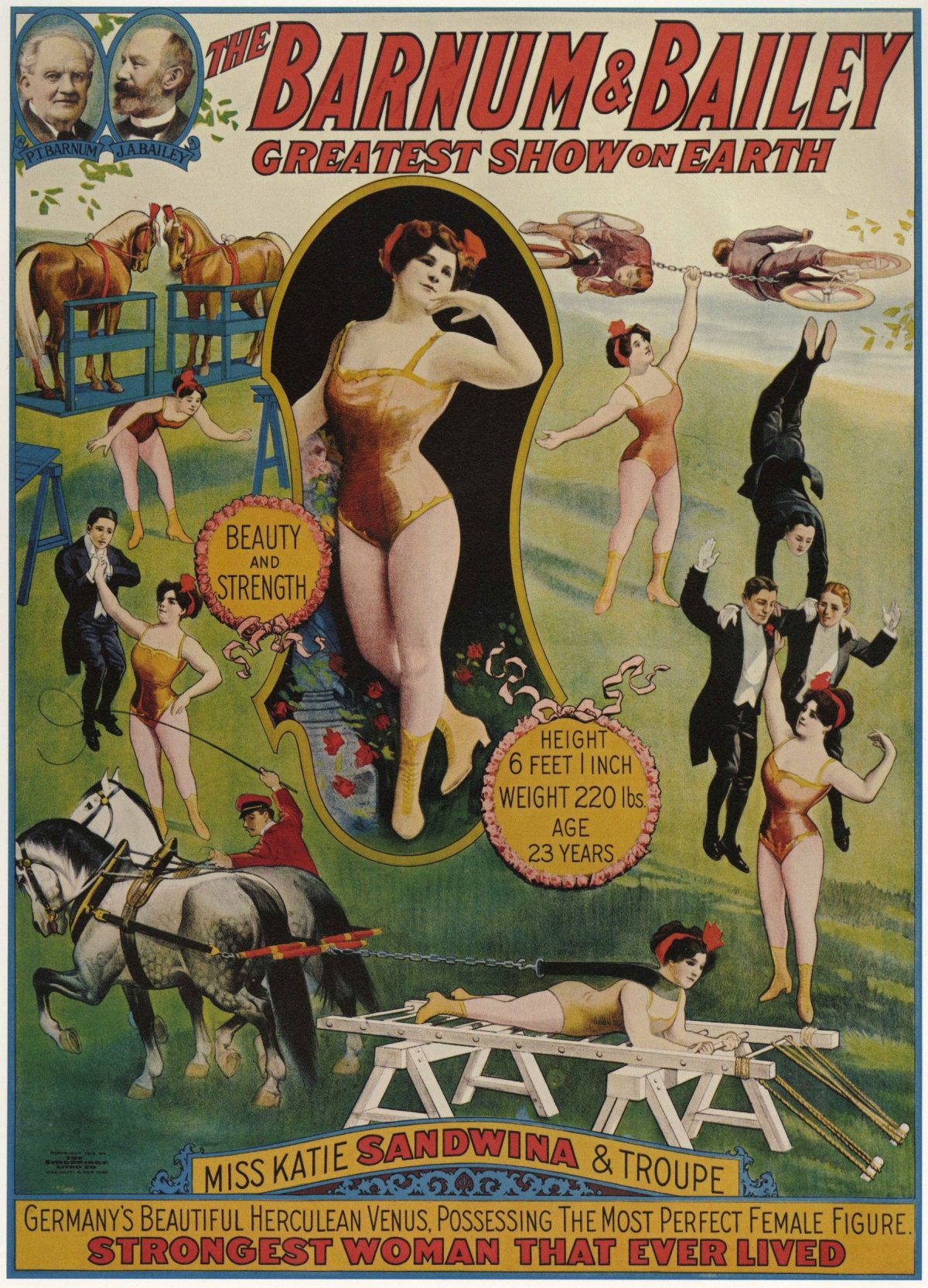

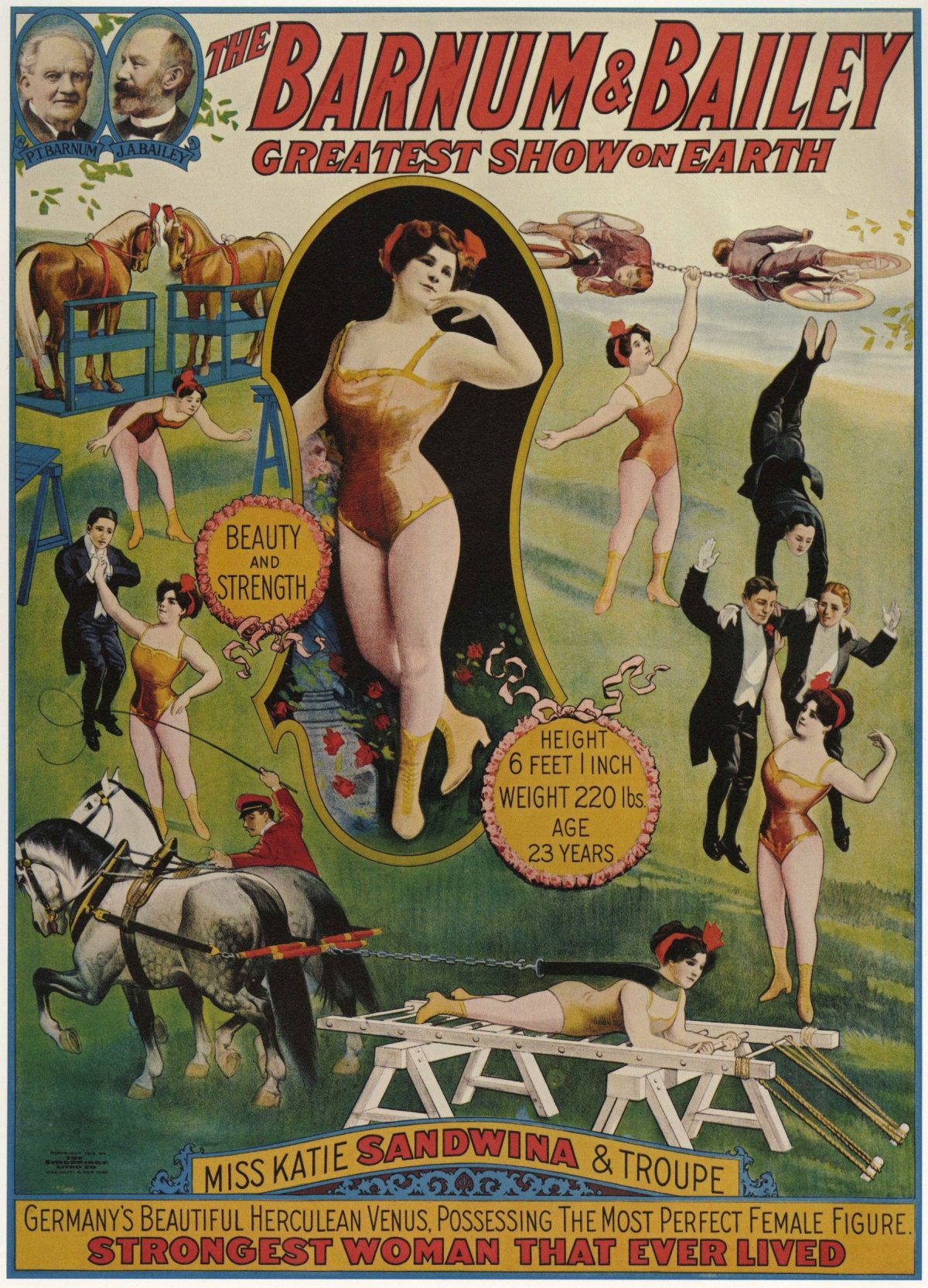

Among the first to break the barriers was Austrian-born Katarina Brumbach, who adopted the name Katie Sandwina after defeating the legendary Eugen Sandow in a weight lifting competition in 1902. Beginning in 1911, she spent many years with Barnum and Bailey, and later Ringling Brothers, performing great feats of strength well into her late fifties. Among her more popular acts was to press her 165 lb husband, Max Heymann, overhead with one hand. Her record-setting overhead lift of 296 lbs (129 kg) was finally bested by Karyn Marshall in 1987, three decades after Sandwina's death.

During this era, female lifters focused more on power than aesthetics. So while strongwomen existed, albeit a rarity mostly confined to circuses and travelling shows, women's bodybuilding was still decades away. Yet even with women like Sandwina and her peers, women were still viewed as stereotypically frail and weak. Just watch any film up until the mid to late 1970s, and nearly every women is a "damsel in distress" who screams and faints at the first sign of danger. It's a truly eye-rolling cliche. The struggle for women who enjoyed fitness and strength training to be accepted continued on.

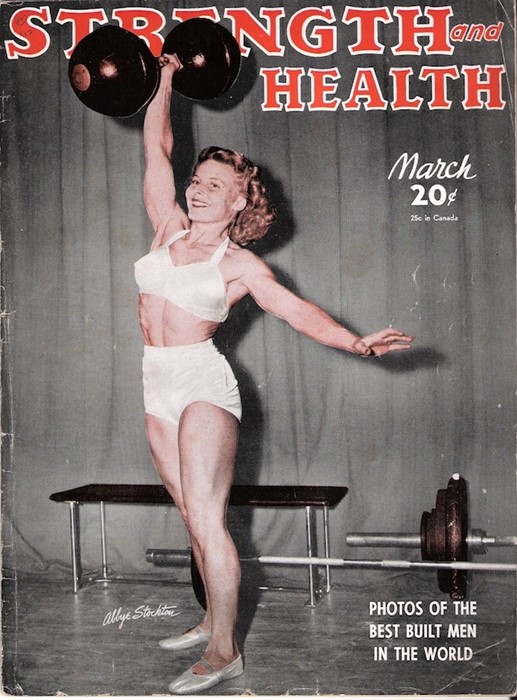

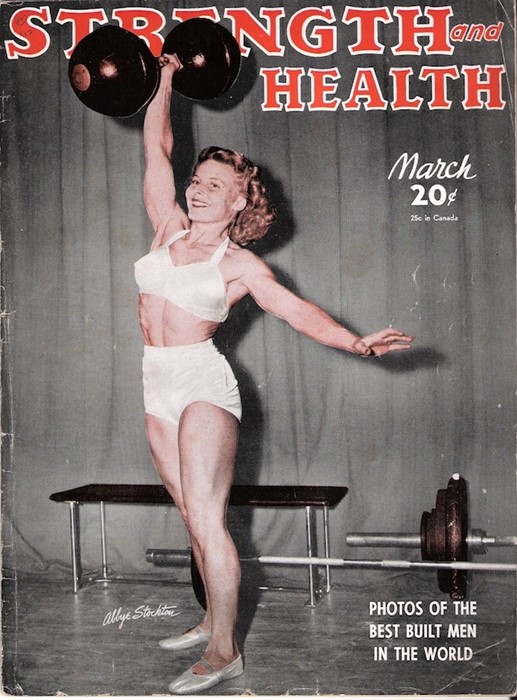

One woman who bucked this trend, continuing to lead the way for other female lifters, was Abbye Stockton. Oddly given the nickname "Pudgy," she was both a strongwoman and early bodybuilder. While her pure strength paled when compared to Katie Sandwina, at just 5'2" and 115 lbs, Abbye combined both strength and aesthetics, demonstrating that muscles were not just attractive on men.

Abbye and her husband, Les (a pioneer in men's bodybuilding, along with the likes of Bill Pearl), were regular fixtures at Muscle Beach in Santa Monica in the 1940s and 1950s.

Abbye even managed to feature on the cover of the March 1948 issue of Strength and Health, which remained the most popular weightlifting magazine in the U.S. before being surpassed by Muscle & Fitness in the late 1960s.

For all the progress made over the decades (centuries, really), bodybuilding and fitness were still an obscure subculture, regardless of gender. Gyms were few and far between, and horrific habits like smoking still ran rampant. The biggest break for mainstream acceptance came with

Pumping Iron, the unexpectedly successful docudrama (part documentary, part scripted drama) which made Arnold Schwarzenegger a household name. Filmed in 1975, covering the Mr Olympia and Mr Universe competitions, it was finally released two years later to critical acclaim.

Pumping Iron not only opened the doors for Arnold to become a megastar, not to mention Lou Ferrigno, who became world famous as The Incredible Hulk a few years later, it also brought bodybuilding into mainstream ... or at least halfway. Absent in the film are any female lifters. The only women I recall seeing in the gym segments are two young ladies sitting on Arnold's back while he does calf raises. While the Mr Olympia had existed since 1965, the first Ms Olympia was not until 1980.

In 1985, George Butler and Charles Gaines, who'd written and produced the first Pumping Iron, attempted to recapture the magic, this time focusing on the even less well-known sport of women's bodybuilding. Covering the buildup to the 1983 Caesar's World Cup, it followed a similar format as the first film with the 1975 Mr Olympia / Universe. The film received far less positive reception, however, as it felt more scripted and less about the training and competition. Rachel McLish, the first Ms Olympia, who'd done more to popularise women's bodybuilding than anyone, was portrayed as a "villain." This came across as disingenuous and out of character for Rachel, in what felt like a cheap ripoff of Arnold's somewhat devious character in the original.

While lacking the authenticity of the first film (which still had its share of scripted drama), Pumping Iron II has its place in helping to bring women's bodybuilding to the masses. As the 1980s progressed, strong, muscular women, like their male counterparts, were becoming more acceptable in pop culture. Sandahl Bergman in Conan the Barbarian, Jenette Goldstein in Aliens, and Linda Hamilton in Terminator 2, are just a few examples. Health and fitness have since become a multi-billion dollar / euro / pound industry. And while this has brought its share of flaws (as noted in my

previous post about supplements), building muscle and being strong is not just for "sideshow freaks." Nor is it confined strictly to men. Health and fitness truly is for everyone!

(Note: I'm expanding this blog into stories about both fitness and history in general, as both are my shared passions. Next post will take a deeper look into what turned into a rather popular thread on my official Legionary Books Facebook Page)

_-_Eugen_Sandow_(1867-1925).jpg)

Comments

Post a Comment